Leadership Chemistry: Catalyzing an Environment That Drives Team Transformation

And Leaving a Legacy in the Process

In This Article:

Leadership is all about creating the right environment, not controlling it

As catalysts, leaders don’t own the results. Their teams do.

Catalytic leaders think “legacy”

Key Application:

A simple, but profound, catalytic leadership application

Everyone in the leadership space, it seems, loves the word “catalyst.” It’s not quite as hip as “disrupter” … after all, it’s been around longer, so it’s aged a bit. But still … “catalyst” (and the adjective form, “catalytic”) still gets traction. It’s a power word.

But I’ve noticed something: As I’ve heard people using “catalyst” in describing leadership, I get a sneaky suspicion that they haven’t actually Googled the word. I’m tempted to quote a line from Princess Bride:

People usually use “catalyst” to describe leaders that light a fire under their teams. With this meaning, the leader is someone who brings energy to the room. They show up with the right mojo, get things moving, create an accountable plan and then rally their troops to press on to achievement. In other words, leaders get results—and by association, they end up owning the results.

Now, to be clear, there’s a lot of good things in that description of what leaders do. A leader’s energy is important, and often is what the team needs most. A leader’s confidence, clarity and conviction about achieving results is often exactly what the team is missing. The ability to get the team unstuck, to break out of the status quo is an apt description of leadership behavior.

But while this understanding of “catalyst” accurately describes much of what leadership does, there’s a critical piece missing in our understanding of a “catalyst”— that also happens to be one of the most important elements in being an effective leader.

How a Catalyst Works

“Catalyst” comes from the world of chemistry. A catalyst is an element that is introduced into a combination of other elements that aren’t reacting on their own. The catalyst causes (or speeds up) a reaction.

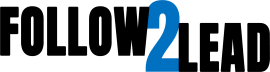

Here’s what it looks like without the catalyst:

You can even add energy to the mix (i.e. turning up the heat), but the compounds don’t interact (or they react at an imperceptibly slow rate).

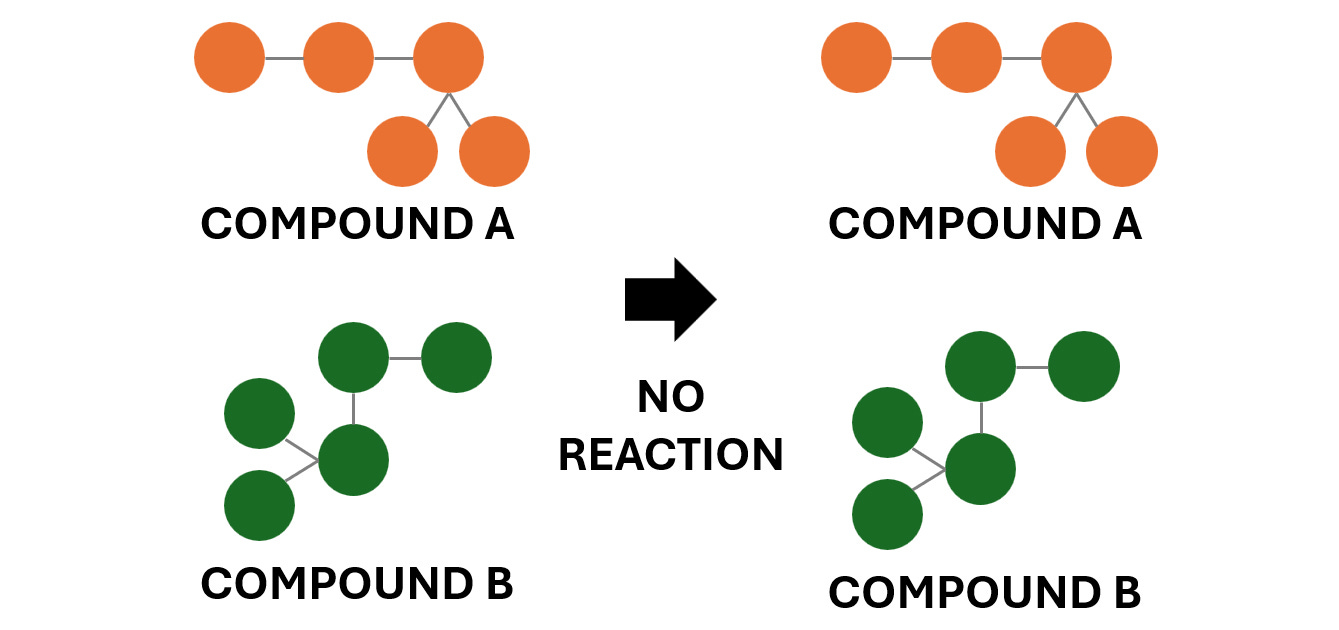

But when you introduce a catalyst, things change:

Technically, a catalyst lowers the activation energy barrier that’s preventing the reaction. Meaning: The catalyst creates the right environment for the reaction to occur, changing the conditions so that the reactants can interact in ways they otherwise couldn’t—or wouldn’t.

This is the distinction in our common understanding. Catalysts don’t add energy, they change the environment and lower the barriers to reaction.

This Is Not Splitting Chemical Hairs

What might seem like an irrelevant nuance is actually a huge distinction, for several reasons. First, catalytic leadership doesn’t come into the room and turn up the heat to get the team to react. Instead, it changes the environment by eliminating the barriers that prevent the team from reacting on its own.

Second, after the reaction you have an entirely different team. Once team members have gone through the process of operating as a genuine team, collaborating at their full potential and creating their own results, they’ll never be the same. And they’ll never settle for being a collection of individuals again.

Finally, in this kind of reaction the catalytic element is not included in the results. In a leadership context, the leader doesn’t experience the results in the same way the members do. Another way to think about this is the leader can now leave the room and the team remains stable. The team now knows it operate on its own without depending on the leader’s direct input.

This is a primary goal of leadership: Leaders operate as catalysts to get the team to a level where they can function without the leader’s direct involvement.

Think: Legacy

This last point is why we would benefit from an accurate understanding of using “catalyst” to describe leadership. It helps to raise the bar on what we try to accomplish as leaders, from getting results (an honorable and valuable leadership activity) to transforming and equipping the team to function effectively on their own.

One of the go-to resources in my coaching over the years has been David Marquet’s book, Turn the Ship Around.

David is a former Navy submarine captain, who transformed the culture and teamwork on a nuclear-powered submarine—a fairly complex piece of equipment and a unique leadership environment. David makes a significant realization about leadership: Navy sub captains were always evaluated by how well their ships performed under their leadership … a relevant metric, to be sure.

But a more important metric was how well the crew performed after the captain departed. He makes a compelling argument that the true test of leadership is how well the crew performed for the next captain. In other words, what leaders leave behind, not what they produce on their watch.

This is part of what we can—and I’m arguing, should—have in mind when we think about catalytic leadership. I ask you to consider this principle in the most common (and most foundational) of leadership challenges: Raising our children.

Cheryl and I did many things right in raising our kids (that as of this writing are 33, 31 and 29). There are also SO many things we’d change if we had a do-over. But one of the overarching principles we parented by truly was a game-changer for us: the realization that our goal was not to get them to do what we say. Instead, our goal was to prepare our kids to be adults. This meant …

We didn’t just have them parrot the rules, we had them explain to us why the rules exist and why they were important to them.

We didn’t just tell them to stop fighting, we made them grant and ask for forgiveness.

We didn’t just tell them what to do, we made sure they understood how our core values can direct them to know what to do; why values are important and how they give us a foundation for life.

We didn’t tell them who they were, we helped them discover who they were as individuals and how to be better versions of who God made them to be.

We didn’t constrain them to keep them from failing, we let them fail and helped them realize what caused the failure and what they would do different the next time. (that was a hard one…)

We didn’t silence them or keep them from expressing themselves, but we taught them never to disrespect anyone when expressing their beliefs and convictions.

I could go on, but hopefully you see where I’m going. My point is that we tried (imperfectly) to catalyze adulthood in them.

One Simple Application

If you’re leading a team, ask yourself this question on a consistent basis:

“What does my team need to be able to do on their own that they currently rely on me to do?”

You may come up with more than one thing. If so, pick the one that represents the highest priority. If you have trouble prioritizing, evaluate them using three criteria:

Which is low-hanging fruit (easiest to implement)?

Which will make the most immediate impact to their performance?

Which has the greatest potential for downstream development?

Then ask yourself:

“Why aren’t they already doing this? What’s blocking them? How can I change their environment so that they start doing it?”

This—changing the environment—is where you apply your leadership efforts.

Peace be with you…

Got a thought about this…?

Looking for More Leadership Insights?

Check out my book Taking the Lead: What Riding a Bike Can Teach You About Leadership